Sacred Symbols: The Folk Art of Norway

Introduction

From the earliest times, people have created symbols to mark meaning and add beauty to the objects in their lives.

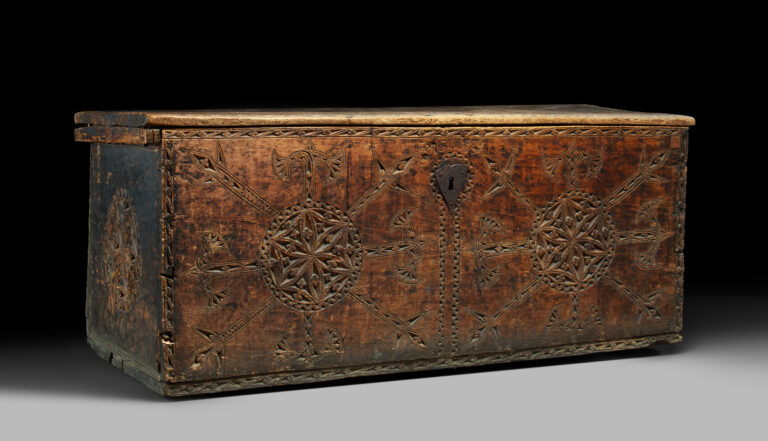

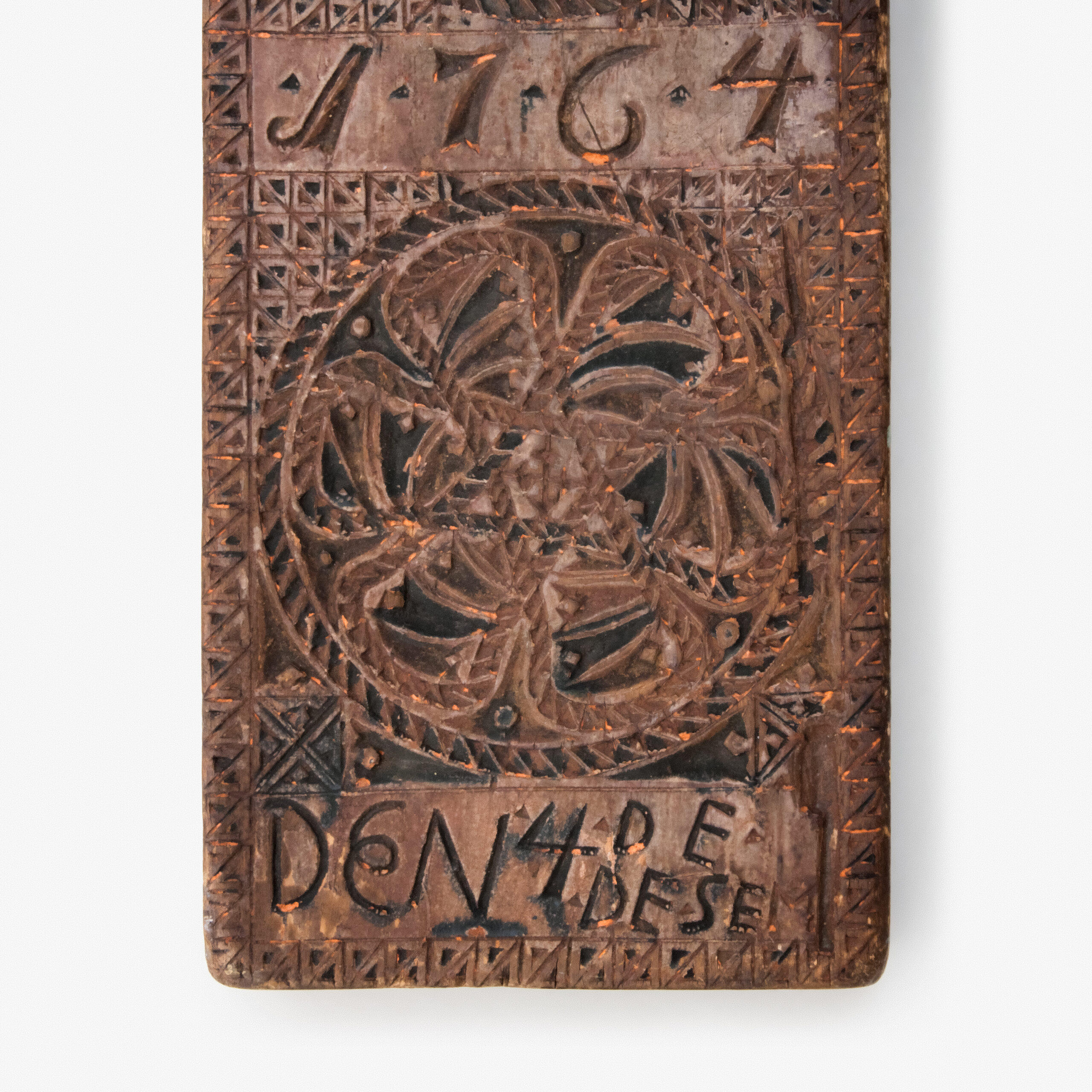

In Norway prior to 1000 C.E., symbols surrounded people every day and, most importantly, on special occasions. Many of the same symbols continued to be used on objects in Norway, and elsewhere in northern Europe, into the nineteenth century. They were often found on wood, horn, metal, and textile objects, especially when those objects were made and used in rituals. The symbols might be formed as the object was made, or added later by carving, burning, engraving, embroidery, or printing. Today, we consider many of these objects folk art.

The motifs came down from the late Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Viking times. The symbols represented and attracted powers that everyone needed throughout life. For instance, one of the oldest symbols used on folk art represented the sun, which brought light and warmth into human lives and stood for good fortune and the creation of new life.

Other symbols long important in rural Norway include motifs of agricultural and human fertility; for protection from unforeseen forces and death; and special to the spirit world, its deities, and the world beyond our own.

This exhibition explores the meanings of symbols on historic objects in the years before Norway converted to Christianity around 1000 C.E. The objects on view are from the collection of Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum in Decorah, Iowa.

The exhibition was curated by Mary B. Kelly and made possible through the generous support of the Walmart foundation and Ruth and Arne Sorenson. ![]()

The Good and the Holy

Some of the oldest symbols represent the sun. Symbols of the sun brought light and warmth into human lives and stood for good forces, good fortune, safety, and the creation of new life in the fields, the flocks, and in the family.

Sun symbols are circular, with four, six, or eight rays. They can be active, whirling left or right, with wavy rays or hooked arms. When they rotate to the right, they symbolize time. When they rotate to the left, they symbolize the seasonal rotations.

Solar worship came with trade from the Mediterranean world to Scandinavia in the early Bronze Age. Researchers have traced this motif along the Danube River and up into the Danish islands, where there are graves of priestesses of the sun, who wore large bronze circular disks on their abdomen. The priestesses used these reflective circles in their rituals, to catch the sun’s rays. Later, this large disk can be seen worn by women on the Viking-age Oseberg tapestry. Round brooches are still worn with Norwegian bunad (national costume).

The Blessing of Fertility

Symbols of agricultural and human fertility have long been important in rural Norway. The “fertile field” symbol, a diamond with four “seeds” in each quadrant, stood for human and animal fertility. Hooks or spirals might be added to the basic motif. Spirals and horned animals were also symbols of these powers.

Horses, symbolizing strength and fertility, appear on objects associated with engagement and marriage. A man might make a mangle board (mangletre) with a horse-shaped handle and present it to a woman as a proposal. (She would use the board in her married life to smooth cloth.) Horse-headed bowls of beer were passed around at weddings to celebrate the union and ensure the success of the couple’s family and farm.

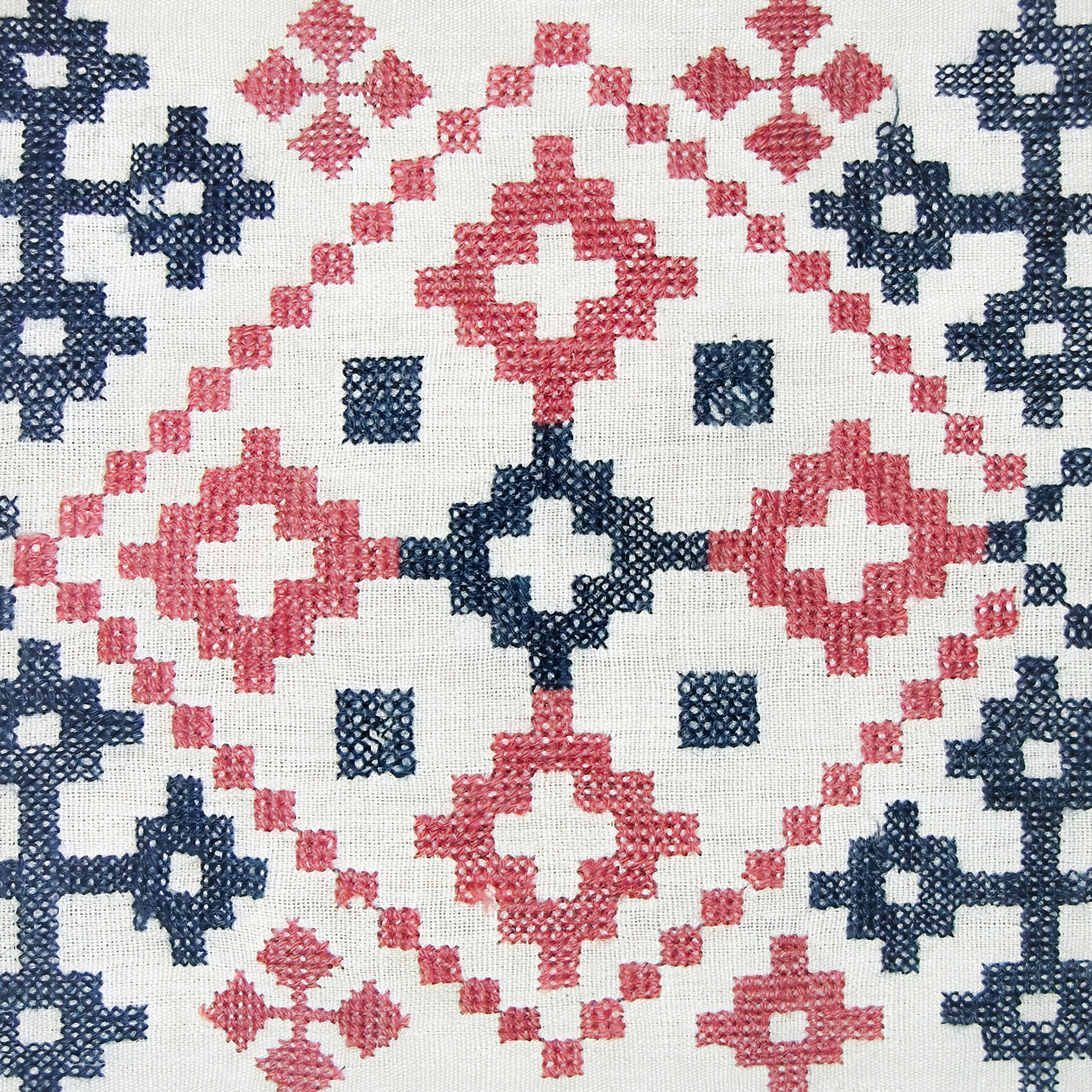

A bride, especially in Telemark, wore decorative cloths from her belt. She embroidered her own cloths and included motifs to enhance her fertility, the fertility of her groom, and that of their farm. Even into the nineteenth century, the newly married couple would sit at the high seat in front of a large ceremonial cloth. This high seat marriage cloth (høgsettebrudeduk) was embroidered with goddesses, who are often shown holding fertility symbols, rhombic forms, the age-old symbol of the womb. The “tree of life” was also popular, representing the transition from single to married life. Red carnations symbolize married love.

The female figures probably represent the pre-Christian goddesses of the Viking Era, called disir or vetter. These were family and guardian spirits, to whom sacrifices were made for luck or fertility of the land. They were special guardians of women and were linked with turning points in a woman’s life: menstruation, marriage, childbirth, and menopause. Women likely memorialized this closeness by embroidering the goddesses on the ritual cloths they used at weddings and other special family feasts.

Protection from Harm

People needed protection from unforeseen events, evil forces, and even death. Symbols guarded barns, granaries, and houses, as well as the people, animals, and products inside. Protective symbols took several forms, but most utilize opposites to confuse the evil forces. Therefore, a zigzag line moves up and down and some motifs whirl in opposite directions. The combination of S and Z motifs are also opposites. Knot and lock symbols were often used to guard against theft.

The openings of clothing often had protective symbols, such as zigzag motifs, to keep evil from reaching the body inside. Sometimes the bedding had woven or stamped designs for added protection. After a mother gave birth, friends brought strengthening food in covered containers covered with decorative cloths bearing similar designs.

Babies were particularly vulnerable and needed protection, which often took the form of symbols on embroidered and woven textiles. After Norway became a Christian country, the ritual of baptism helped protect the child. On the way to church and during the ceremony, he or she still needed to be swaddled in symbols on bands, blanket, cap, and baptismal wrap.

Knots, such as the valknut and olavsknut, could protect the treasured contents in boxes, or even help bind a loved one to you. Checked and netted symbols called “mara locks” (in both male and female versions) stood guard against the evil from the mare, a spirit that tormented people in their sleep (nightmares).

Access to the Divine and the "Other" World

Special transition symbols assisted humans in their passage through life’s stages. They were used on textiles and other objects for baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Symbols linked earth and sky and people to the spirit world, its deities, and to the world beyond their own.

One important transitional symbol is the “tree of life” with its roots in earth and its crown in the heavens. Sometimes with birds or people in its branches, it was old long before it was brought into Scandinavia. With it came the image of a triangular-skirted female deity whose arms were upraised to the heavens and her feet firmly on the earth, bridging the two worlds. Birds, whose homes were in the sky, were also symbolically linked to the spirit world. Horses were sometimes seen as embodiments of the trip into the “other world,” the world of the dead.

The equal-armed cross was not always the Christian cross. It was adopted by the “new” religion after the fall of Viking society. This symbol’s earlier meaning was a crossroads. The crossroads represented not only roads leading toward the points of the compass – north, east, south, and west – but also the way to the upper world and to the underworld. Shamans and priestesses in Viking times approached the crossroads in order to access the spirit world beyond our own.

The world of the ancestors was never very far away from the farms of rural Norway. At death, textiles facilitated the final journey of life. Symbols were woven or embroidered onto cloths arranged in the shape of a cross over the coffin. Mourners would give a final toast to the deceased before a candle on the coffin directed the soul upward.

Symbols and Meanings

While symbols continue to be recognizable and meaningful over time, the meaning of some symbols has drastically changed based on their use.

Swastika

Since late in the Stone Age (roughly 9500 to 2000 B.C.E.) and throughout Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and North America, the hakkekors (swastika) was used as a symbol. Although the precise meanings varied, it was most commonly used as a symbol of goodness and holiness, good luck, or the four directions.

In Germany in 1920, the Nazi Party officially adopted the swastika as their symbol. Because of the violence and death associated with the Nazi Party and World War II, the swastika has become one of the most hated symbols in the world. Its meaning has changed forever, and it is no longer acceptable to use.

Equal-Armed Cross

In Viking times (800 to 1050 C.E.), the equal-armed cross was a familiar symbol. It stood for the crossroads. This special place not only represented the roads to the north, south, east and west, but also to the heavens and to the underworld. Thus, shamans and priestesses approached the crossroads in order to access the spirit world beyond our own.

People believed that when they died, they too would cross into the spirit world. Two ceremonial cloths were symbolically crossed over coffins. When Christianity arrived in Norway, a cross with one longer arm became the symbol for the new religion.

Acknowledgements:

The sponsors for the exhibition at Vesterheim in 2009-2010 were:

Humanities Iowa and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views and opinions expressed by this exhibition do not necessarily reflect those of Humanities Iowa or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The Royal Norwegian Embassy

Kate Nelson Rattenborg with matching funds from Thrivent Financial for Lutherans

John and Veronna Capone

Paul and Carol Hasvold

T. Eileen Russell

Jane Y. and John Connett

Carol O. and Darold Johnson

Special thanks to:

Telemark Museum, Skien, Norway; Dr. Mikkel Tinn; Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, Arkitektur og Design, Oslo, Norway; Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo, Norway